When Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni had announced the title of her latest novel on her Facebook page and asked fans to guess who the titular queen could be, the answers had ranged from Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi and Rani Chennamma of Karnataka to the Tuluva queen Abbakka Chowta of Ullal (present day Mangaluru), and even a vague “anyone from the family of Bahadur Shah Zafar”. So the Indian-American author’s decision to bring story of Rani Jindan Kaur of Punjab to the world as the heroine of her latest novel, The Last Queen, was a well-thought-out surprise.

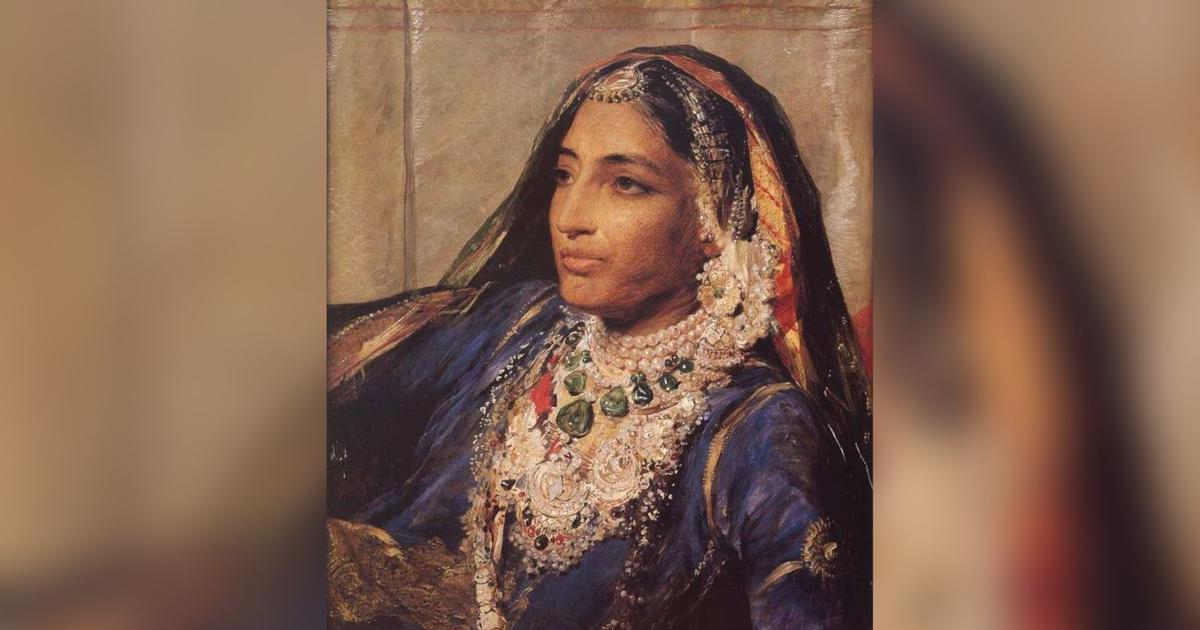

The youngest and last wife of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, founder of the Sikh Empire, Jindan Kaur has found relatively less space in history books (like many other women leaders from the past). While there have been several works on kings and male heroes of the eras gone by, those on the important women of history have been rare. There’s Ira Mukhoty’s brilliant Daughters Of The Sun (2018) that brought the untold lives of Mughal women to the page, while her debut Heroines: Powerful Indian Women of Myth and History (2017) told us tales of the might of female leaders from Raziya Sultan to Meerabai.

The Women Who Ruled India (2019) by Archana Garodia Gupta threw light on the lives of several queens from around the country, while stories of Rani of Jhansi’s valour remain ever popular. It seems that Jindan, though, hasn’t found more than a passing mention in popular historical narratives. Navtej Sarna’s The Exile: A Novel Based on the Life of Maharaja Duleep Singh traced the life of her son who lost his kingdom at just eight. And one of the few non-fiction works to briefly cover Rani Jindan has been William Dalrymple and Anita Anand’s 2016 work, Kohinoor – both books that Banerjee Divakaruni cites as invaluable resources in her acknowledgements.

Sense of agency

Tracing her life starting from her childhood days in 1800s Gujranwala, near Lahore, the story takes readers through cities, states, countries and decades as Jindan Kaur takes on every challenge that comes her way with determination and fights her way out of it, whether it be the jealousy of a fellow queen or the might of the British. Following Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839, three maharajas, one maharani and several high-ranked ministers lose their lives in a greedy quest for the crown, in the span of just five years.

It ultimately settles on the head of Ranjit Singh’s last surviving heir, the five-year-old Dalip Singh – making his mother the regent queen of the Sikh Empire, a role she takes on with passion. Jindan, a kennel-keeper’s daughter, was among the few medieval Indian women to renounce the veil at court and address her forces directly.

Like some of Banerjee Divakaruni’s earlier works, The Last Queen follows a first-person narrative, letting readers learn of the peak and fall of the empire through Jindan’s eyes and emotions. There is a huge roster of characters – apart from the Sikh ruler and his family, the Dogras of Kashmir and the Jat Sandhawalias play significant roles – and many storylines to keep track of, but the author manages to tie in each plot adequately.

The attention to Jindan’s personal relationships, whether with her brother Jawahar, her husband, son, a favourite fellow-queen Guddan, or even her personal maid Mangla, brings in a much-needed emotional angle, one that could have been lost in a tale of valour and bloodshed.

Most importantly, the novel gives Jindan a sense of agency – for the most part, she is the master of her own decisions. As a young teen, she wants to marry Ranjit Singh not because her father plans to give her away with promises of her beauty but because she has fallen in love. “I want the Sarkar to like me, but not in the way Manna wishes,” she maintains.

Years later, after the widow Jindan takes over as regent, she finds a lover in Lal Singh, a nobleman at court. Although it comes after much emotional turmoil, she is the one to make the first move, from the first outstretched arm to the first kiss. “Something wild inside me makes me throw back my veil and look into Lal’s eyes. This is the first time I’ve knowingly enticed a man.” It is her choices, her mistakes and decisions which she takes full responsibility for, that make Jindan the fearless, strong woman she is.

Driven by action

Compared to Banerjee Divakaruni’s past books The Forest of Enchantments and The Palace of Illusions, centred on the mythological figures of Sita and Draupadi, respectively, this one is a much lighter and quicker read, one that can be consumed in a single sitting. Action drives the story, and the writing is more fast-paced and casual as opposed to the formal, descriptive narratives that characterised her previous works.

While the first three parts – “Girl”, “Bride”, “Queen” – of the four-part novel play out in exquisite detail, it makes the last few chapters of “Rebel”, that cover her years as an exiled ruler in Nepal and later in Britain reunited with her son, seem like more of a longish epilogue due to their short length. This somehow makes the ending seem a bit rushed, leaving the reader wanting more. The small grouse aside, the author’s mastery with words and her gift of weaving in fictional moments while staying true to the original premise – or history, in this case – continues to shine through.

“People revered his father as the Lion of Punjab, but his mother is the one they should have called Lioness. In her way, wasn’t she braver than Ranjit Singh? Didn’t she fight greater obstacles?” Jindan’s son ponders as he sends the last of her ashes off into the sea on his sea voyage back to Britain. The greatest victory of The Last Queen is perhaps that it leaves the reader eager to know more about the real life of this royal rarely spoken of outside the kingdom she called home.

There are forgotten histories that need to be known widely, and Rani Jindan’s is undoubtedly one of them. In the absence of a definitive biography, Banerjee Divakaruni’s novel seems like an apt place to start.

Source: Scroll.in

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.